Interview

Initiation into Ecstasy An Interview with Hiah Park - Korean Mudang by Nina Otis Haft

|

Hi-ah Park is a Korean mudang (shaman) who specializes in the art of ritual dance. She has worked as a court musician and dancer in the Korean classical tradition, has received a

master of arts degree in dance, and has taught Korean dance and ethnology - as well as sound and movement improvisation - in universities.

Since her initiation as a Mudang in 1981, Park has traveled extensively, performing shamanic ritual dance, trance dance, and traditional Korean dance throughout the United States,

Europe, and Korea. She also conducts lectures and workshops dealing with spiritual healing and techniques of ecstasy.

Mina Otis Haft:

Hi-ah Park: No one knows exactly when Korean shamanism began, but there is evidence that it was practiced as far back as the Neolithic Era. It had long been

practiced as an indigenous way of life before it became the traditional religion of Korea during the Three Kingdoms Period (57B.C. - 676 A.D.) Later the aristocrats abandoned

shamanism and embraced imported religions including Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. However, the common people have continued to practice shamanism to this day. Mina Otis Haft: You are a native Korean. How did you come to live in the United States? Hi-ah Park: In 1963, I became the first woman to beadmitted to the Korean National Classical Music Institute as a court musician and dancer. I was invited to the United States in 1966 to perform and lecture on classical Korean music and dance at the Asian Academic Institute of Northwestern Nazerene College in Idaho. Later, I was offered teaching positions - in the dance department at UCSD in 1984. These positions gave me the opportunity to teach sound and movement improvisation. Mina Otis Haft: Were you trained as a child to become a mudang? Hi-ah Park: Actually, I was raised in Korea as a Christian; I didn't become a mudang until long after I had moved to the United States. However, my first experience of shamanism was in early childhood. A neighbor of ours had a severe case of hiccoughs that he had not been able to stop for several days. I remember that a mudang came to the man's house and waved her sword around his head - chanting, singing, dancing. At that time, I did not know what a mudang was, but I was literally entranced by the shaman's performance. I found it difficult to talk about this experience to anyone becouse of my staunch upbringing as a Christian. Shamanism and supernatural activities were viewed as superstition, so I kept this experience as a seperate reality deep in my heart.

|

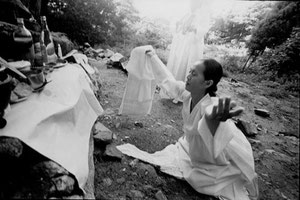

Hi-ah Park, wearing a traditional Korean mudang outfit, performs a shamanic dance.

During her initiation as a mudang, Hi-ah Park experiences an ecstatic trance journey into the milky way.

A Ritual Dance of Death and Transformation

The flyer I saw advertising Hi-ah Park's workshop on Korean ritual dance and ecstatic movement showed her in traditional Korean costume with an ancient, piercing look on her face. She is, in fact

a youthful woman of fifty years, an internationally known dancer, a film actress, the mother of two daughters, a mmartial artist, and a travelling shaman.

As a dancer and martial artist mysef, I have always found movement to be my interface with spirituality. For that reason, and because I was intrigued with the idea of experiencing ecstasy, I

decided to attend one of Hi-ah's workshops in Berkeley, California.

The group that gathered for the workshop was larger than Hia-ah had expected. After we sat down in circle, we took quite awhile introduction ourselves and speaking about why we were there. Hi-ah dialogued with each one of us - questioning, challenging, reflecting, and playing - seemingly probing for the root that each of us sought to tap. Over and over, she reminded us that if we did not know why we were really there, we might as well take our money back and leave. This introductory process turned out to be the foundation of our ritual work/play together.

Then Hi-ah donned her traditional Korean shaman's costume - a light and voluminous gown of rainbow-colored silks, a gold embroidered waistcloth, and pointed white slippers. She invited us to join her in an invocation of the spirits. Bells and fan in hand, she led us in dancing, chanting and making music. Next she called us up, one by one, to perform a ritual dance of death with her. Each time, she extended a fistful of colored silk flags and asked the person to choose one. Based on the flag selected, she offered that person a matching robe to wear and then tailored the dance to meet his or her needs.

She began by engaging her partner's eyes in a timeless embrace. Then, wooden sword in hand, she became the warrior, the hunter, the lover, the mirror of that person's deepest fear. Raising the energy of the confontation by slow, intensifying concentration, she danced with each partner until his or her surrender was complete. Finally, with the loving and truthful embrace of a spirit godmother, she cradled her partner into a newborn existence beyond fear.

Knowing everyone's struggles from the earlier talking circle allowed me to participate in each of their transformations, as I watched them touch their fears and release those fears in joyous celebration. We finished our day together with a group dance, full of playful freeform movement, chanting, and drumming.

Hi-ah Park: It wasn’t until I was a graduate student in the UCLA dance department in 1975 that I began to integrate that childhood experience. One day in class, Allegra

Snyder (chairperson of the dance ethnology department) asked us each to remember and then describe the most extraordinary experience in our lives. As I closed my eyes in the meditation process, I

entered an altered state. My body started to shake uncontrollably, not from nervousness but, rather, as if someone was shaking me. As I talked about the experience of seeing the mudang, I felt as

if someone else was speaking through me.

Later I experienced a similar physical sensation while watching a film titled "Pomo Indian Sucking Doctor." I immediately recognized that the Pomo Indian's healing ceremony was related to the

dancing and chanting I had observed as a child.

After those incidents, I began to frequently experience physical trembling and inner vibrations that frightened me. Until then I had never thought it important to talk abut my childhood

experience, but I now found that it was necessary to do this if I was to understand myself. I began to explore who I was, where I came from, how I got here, and where I was going.

Mina Otis Haft: It sounds as it you experienced a spiritual awakening. Was this when you chose to become a mudang?

Hiah-Park: Actually, I didn't choose to be a mudang; it chose me. When I began studying shamanism in 1975, I had neither the wish nor the intention to become a shaman. I

initially considered the whole process solely as an artistic endeavor, yet everything I encountered along the shamanic path seemed to create a thirst in me for spiritual fulfillment.

I became a mudang after I was called to the profession through sinbyong, or initiatory illness. Actually, I had to experience several periods of initiatory illness, because I didn't understand

what was happening to me. My first sinbyong attacked me when I was nineteen, after I broke off the relationship with my first lover. A big tumor developed on my coccyx, and I completely lost my

voice and couldn't move for about three months. Then, after awhile, the tumor mysteriously disappeared.

The second sinbyong occurred when I was thirty-three. I began to suffer from tedium and loneliness, without knowing any meaning to my life. My interest in mundane affairs and domestic chores

waned completely. I suffered unbearable loneliness and longed for the mountains.

I spent many nights weeping endlessly or dreaming of impending death. In my dreams, I was imprisoned in the underworld and chased by wild animals. For about nine months, I endured sleepless and

restless nights, until I had an incredible, lengthy dream of an ancient royal funeral procession.

My insomnia stopped right after this mysterious dream. I was happy without any specific reason. I felt elevated into the air, as if somebody was lifting me. After this funeral dream, my dream

scene started to change into lighter, celestial ones.

In one unforgettable dream journey, a white unicorn with wings took me through the Milky Way to an incredible, infinite space of deep, jet-dark indigo. In that place, I heard a deep and resonant

voice ask me, "How are the people down there?" I still remember clearly the conversation with that invisible voice, and the ecstatic feeling I had. Then the voice told me I had to go back to

teach the people love. I felt boundless joy and, at the same time, sadness that I had to go back. Without any sense of waking up from a dream, I found myself in my bed. For awhile, I was obsessed

by this dream and felt very connected with that other reality. Although I couldn't understand it, the other space was so clear that I now felt as if my waking state was the dream.

Woman who become mudang challenge the traditional Confucian

values of Korea.

Mina Otis Haft: Can you explain how your initiatory illnesses differ from "normal" illness? The illness you describe sound like the ailments of many woman trapped by sex-role stereotypes.

Hiah-Park: They were something like that. In Korea, women are subjected to great suffering due to the very repressive Confucian society. They are exceptionally ripe to find a new role for themselves, and the role of the shaman breaks all the traditional rules and stereotypes. Therefore, I think the female shaman was the first truly liberated woman. I believe that sinbyong happens because a person's spiritual body is starving from a lack of inspirational creativity. The initiatory sickness allows her to escape from the world and withdraw into the darkness, in order to experience her own rites of passage. In order to become a shaman, the person must go through years of introspection, personal torment, and progressive spiritual development.

Mina Otis Haft: Have woman always taken the role of mudang in Korean society?

Hiah-Park: In Korea today, almost all shamans are women. In the distant past, there were male mudang as well as female ones, but, over the centuries, male mudang have become much rarer. Some people say this change occurred because women were more competent in appealing to the gods.

Mina Otis Haft: How are woman more suited for shamanic work?

Hiah-Park: It is not gender that makes a woman superior but, rather, her access to the feminine principles of spirituality which makes her an essential bridge between this

world and the

states of bliss. In traditional Korean Society, women were not educated as much as men and, therefore, never became alienated from their intuitive and psychic powers by years of

over-intellectualization. I had to unlearn twenty years of education before I was ripe for initiation.

Mina Otis Haft: At the time of your last illness, you were living in southern California, but you were initiated ac a mudang in Korea. How did that come about?

Hiah-Park: As a dancer, while I was living in southern California, I received several requests to perform shamanic rites for the Korean community-even though I had not yet

become a shaman. My first ritual performance was in June, 1980, at the Mingei International Folk Art Museum in La Jolla, California. I was surprised when Mr. Zozayoung, director of the Emile Folk

Painting Museum in Korea, respectfully introduced me as a mudang, particulary since mudang are looked down on in Korea. I was concerned about how I was going to perform the ritual, but when it

came time to give the actual performance, I somehow knew what to do.

During the next year, I performed two more kut in California. Each time, the spirits entered me in a most powerful way, guiding me to perform rituals which I only later learned the meanings of.

After these ceremonies, I sensed deeply that I could not treat these spirits, in me lightly.

Every time I returned home from these performances, I felt oppressive aching in my shoulders and pelvic area. There was a great weight on my chest and I felt as if someone or something was

binding my body. Then I became completely incapacitated, unable to do even the simplest domestic chores. I was sick for two months and I knew I needed help.

Since I'd had two previous illnesses similar to this one, I intuitively knew that this was not something a regular medical doctor could handle. The clarity, freedom, and heightened awareness I

had experienced during the rituals conflicted with the rationalizations, anger, fear, and defensive feelings that plagued my normal state of consciousness. The conflict had spawned a

psychosomatic ailment.

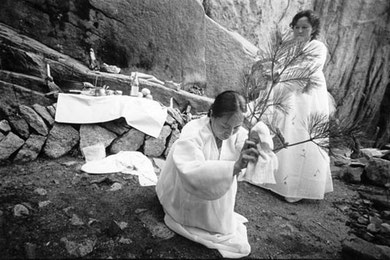

Hi-ah Park and Kim Keum-Hwa, her godmother, at

Hi-ah's initiation cermony

During this illness, I had three consecutive visions. In my second vision, I saw Tan-Kun, the heroic founder of the Korean nation, sitting in a meditation posture within a yurt and wearing a

red hat and rote. As I gazed intensely at that figure, we became one; then I saw myself sitting as Tan-Kun. This clear vision of Tan-Kun convinced me to visit my homeland after an absence of

fifteen years.

I didn't have any specific plan for my visit. However, from its start, everyone I met and everywhere I visited turned out to be connected somehow with shamanistic practices. Within a week, I was

introduced by a friend, Professor Choi Jong-Min, to Kim Keum-Hwa, a well-known Hwanghaedo manshin (shaman from a western province of Korea).

When Kim came into the room in her house where I was waiting, we both shuddered. She told me she had the sensation that her spirits wanted to talk with me. She brought in her divination table and

started to pronounce oracles: “Rainbows are surrounding in all directions. The fruit is fully ripe and can't wait anymore!” She told me I was lucky to have surrendered to the spirits' orders and

to have come to her. Otherwise, she said. I would have died, like an overripe fruit that falls onto the ground and rots.

My body started uncontrollably swaying in a circular motion. With tears running down my face, I tried to hold my knees still with both hands, but I couldn't stop the swaying. Kim continued to

explain that I had disobeyed two times previously and, consequently, had had to go through unbearable pain and loneliness and near-death experiences. She warned that I should not resist

anymore--the third time, there is no forgiveness. It was absolutely essential that I undergo the naerim kut without delay.

On a more positive note, Kim told me she saw double rainbows stretched around my head, celestial gods surrounding and protecting me in four direction, and warrior spirits descending on me. She

said that the warrior in me was so strong that I would want to stand on the chaktu (sharp blades of the initiation ceremony). She predicted that, in the near future, I would be a famous shaman

and I'd travel all around the world. Then she set a date for the initiation - June 23, 1981. In less than two weeks, I was transformed into a new shaman.

Mina Otis Haft: Was there any other preparation or training before the initiation ceremony?

Hiah-Park: My godmother, Kim Keum-Hwa, asked me to eat no meat during the week before the ceremony. As in the previous rituals, in the United States, I didn't know what would happen-but I was determined to find out what power had brought me here and what the meaning and purpose of my life were.

Mina Otis Haft: What happened in the ceremony ?

Hiah-Park: In the morning, I bathed in a cold mountain stream, then climbed Mt. Samgak (located to the north of Seoul) with my godmother. At one point, she asked me to climb

up a steep cliff to get a branch from a pine tree. This task was the first test of the day. I did as she asked to receive Sanshin (the mountain spirit). We talked as little as possible. At the

mountain altar, I offered rice, rice cake, three kinds of cooked vegetables, fruits, candles, incense, and mak-gholi (homemade rice wine). As my godmother chanted and beat a small gong, I held up

the Sanshin Dari, a long piece of white cotton cloth called minyong (white cotton bridge) through which the shaman receives the mountain spirits.

My body started to quiver uncontrollably-a sign that the spirit was entering me.

I completely surrendered to the spirit, turning off my internal dialogue and entering into inner silence. I sensed light coming from every direction, and I started to feel drunk with the spirit

in me. It was the dramatic close encounter with the separated “Lover” at long last. I felt the ultimate completion of my primordial self before separation. I knew that the spirit loved me and

forgave my long resistance to accepting it. Bathed by the light of spirits, I felt clean and reborn. I practically flew down the mountain. I joined the group of shamans and guests in my

godmother's house at the foot of the mountain. I was the sole initiate. We began with a short ceremony invoking and greeting the spirits, followed by the huhtun kut (purification ritual). The

huhtun kut is conducted to cleanse and humble the initiate, in order to dissolve the infantile image of her personal past and prepare her for transformation into a pure spirit of unlimited power.

The ritual started with drumming and chanting, while the shaman's assistants put a basket of cooked millet on my head. Then I danced in a circular motion toward each direction, ending the dance

by throwing the basket. This process must be repeated until the basket lands in an upright position - that's the sign that the evil spirits have been repelled. It wasn't easy in the beginning.

The weather was very hot, and I was wearing full Korean costume. Moreover, I felt self conscious and a little ridiculous in front of all the onlookers. I kept failing until I couldn't bear the

embarrassment anymore. Then, suddenly, something magical happened - all the onlookers disappeared from my view, I felt a point of true fire in my center, and I achieved complete tranquility.

Finally, the basket landed correctly.

The initiation ceremony continued with an examination to test my psychic ability and to determine it I could identity the deities who had descended on me. After I revealed all the spirits (sun,

moon, stars, mountain spirits, high robility, ancestors, etc.) through dancing, accompanied by drumming, my godmother gave me the final test. She asked me, “Where are your bells and fan?” When I

hesitated, she teased me for trying to figure it out. She said that "too much time in the university" was clouding my nonrational, intuitive, and all-knowing self. Then I moved into an ecstatic

deep trance, and I found the bells and fan hidden under the big skirt of the drummer.

Next they put seven brass bowls with identical coven onto a table. My test was to uncover the bowls in the correct order. While dancing to drum accompaniment, I started to touch the covers.

My hands followed the energy. Under the first cover that I removed, I found clear water-which one is supposed to uncover first and which symbolizes clear consciousness and divine purity. I danced

with that cover, then opened the rest of the bowls in this order: rice, ashes, white beans, straw, money, and filthy water. My godmother interpreted what each meant. Rice is for helping peoples

live. Ashes are symbols of name and fame. Beans and straw feed the horse for the shaman's journey and are a good omen for the successful growth of the new shaman. By picking clear water first and

filthy water last, I showed purity of consciousness and successfully passed the test. I saluted, with a big bow to my godmother and her assistant. Then I sat in front of my godmother, who

unbraided my hair and braided it again, symbolizing my rebirth as a new shaman.

The day continued with many more rituals, but I will only describe the chaktu kori (sharp blades ritual) - the final test and the highlight of the kut. During the ceremony before the chaktu, I

could barely hold my spine up and I felt my energy leaking out. My will was dissolving, removing the last internal barrier against my warrior spirit. My godmother understood what was going on

with me, so she started to put her own costumes onto the other participants to make them dance. Although I could hear the laughter of the people dancing, I felt as if I was in a dream, watching

them. Somehow, I managed to drag my body to the altar where the tangwha (shamanic iconographs) were hung. As I sat there, I saw the paintings of the deities disappear and reappear as real living

beings. I saw the mountain spirit standing before me, smiling. Although he was silent, I could hear him speaking to me. He touched my shoulder as if I was a little child. I felt full of affection

and would have gladly remained there as a servant forever, but he gave me the feeling that I had something unknown to accomplish.

Then, suddenly, all the spirit warriors depicted on the iconographs came into my body. I felt I had been transformed into another being. I still felt as if I was in a dream, but I could hear the

noises of the people preparing the chaktu tower outside.

I knew that soon I would be expected to dance on top of the chaktu tower, a structure consisting of seven layers: drums, tables, jars, and pots, with wooden boards in between - and a pair of

sharp chaktu on top. When finished, the tower was about seven feet tall. My godmother pulled me next to her - she started to sing an invocation song and then she gave me two swords. I took them

and started dancing. By using the swords as a transformational tool, I was able to recharge my energy. I contacted the fear of death that lay deep within me, integrated that emotion, and allowed

myself to die - then I was born again with the warrior spirit.

After I did the sword dance for awhile, I gained sufficient energy to enter the kitchen, where the two big chaktu cleavers were waiting, wrapped in red cloth. As soon as I unwrapped the chaktu, I

felt within me an unknown presence who knew no fear or limits. I started swinging the heavy, sharp chaktu against my arms, legs, face, and mouth.

Although these same blades cut wood easily, they didn't harm me. All crewed, the onlookers were frightened and spellbound. After I proved that nothing could harm me, I did the most vigorous dance

of my life. At the peak of the dance, I seemed to fly up to the top of the tower, where I danced barefoot upon the chaktu. People later told me that my eyes didn't look human - that they had the

luster of a tiger's eyes.

As I stood barefoot on the sharp blades, I gained absolute freedom in time and space. Some of the onlookers cried because of the unbearable intensity of the experience. When I came back, we

released the tension together in ecstasy and tears.

Mina Otis Haft: Your initiation as a mudang sounds very complex and traditional. Is it necessary for your students to belong to the ancient Korean religion in order to work with you?

Hiah-Park: Not really. Although I was initiated as a mudang and have great respect for the tradition, I think of myself as a spiritual midwife and a global shaman. I believe that today we must look beyond the organized religions and the attachments of culturally prescribed spiritual practice. Traditional religions attempt to define and direct our religious experiences. In contrast, the essence of shamanism is to make accessible the indefinite and to explore realms that go beyond language and social organization.

Mina Otis Haft: Can you give us an example of how you function as a spiritual midwife?

Hiah-Park: Last spring, the Women's Alliance invited me to the Women's Solstice Camp in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I performed a ritual ceremony. Before I began, I

picked seven participants and asked what they wanted to accomplish in the ceremony. One of them told me she wanted to cure her breast cancer. During the ceremony, as I was possessed by the

warrior spirit, I went into the audience and grabbed this woman's hands, pulled her to the front, and then danced on her chest until she completely surrendered to the spirit.

A week later, the woman came to a workshop I was giving in the Bay Area. She explained that after what had happened to her at the Woman's Camp, she had gone to the hospital for an examination.

Three doctors examined her, but none of them found any signs of cancer.

This woman was ripe for opening and ready to transform herself; that is why my psychic surgery was effective. My psychic surgery only works for those who are willing to confront their dark side

and surrender to the primal spirit. When I say “psychic surgery”, I don't mean cutting into the person - my surgery involves cutting through the fear, stitching up the psychic tears in the fabric

of mind, body, and spirit.

Mina Otis Haft: Your shamanic work seems to incorporate, yet move beyond, the structure of the traditional kut.

Hiah-Park: Yes, you can say that. In June, 1988, I was invited to an international symposium in Munich called "Art and Invisible Reality" to give a ritual dance performance.

Just before the beginning of the ritual dance. I suddenly got an inexplicable physical cramp in my legs, unlike anything I had experienced before. I couldn't ever stand up. Everyone was very

disappointed. The master of ceremonies, Johannes Heimrath, asked me, “Can you perform just for five minutes?” I responded, “Yes,” without even thinking, “How?” I gave up the idea of doing a full

ritual dance -instead, I let the spirits move me according to the participants' needs. For the Germans, who are so time oriented, this meant I was guided to slow down. I dance serpentine, slow

movements, as if lifted by an invisible force. The dance vibrated with dynamic fire, evoking pathos, the spiralling energy. It was a timeless bridge between life and death.

I find that the more I tap into the primordial state, the less rigidly I follow the traditional fixed form. Even before I became a mudang, I realized that music, dance and drama belong not only

to the realm of aesthetic beauty but also to the realm of spiritual realization which leads to ecstasy. Therefore, my teaching method has emphasized the connection between breath, mound, and

movement in relation to human behavior and the transformative potential of these very natural human activities.

Mina Otis Haft: It sounds as if ecstasy is very important in your work. Can you explain more about ecstasy?

Hiah-Park: Ecstasy is a sensation which is encountered in our hearts. It is seeing and hearing with the heart rather than just with eyes and ears. It is also a flame which

springs up in the heart out of longing, to see and to become one with its truth (God). The purpose of my work is to share this experience with others. Dance creates a joy pouring forth from

within, a deep sense of beauty, a state of ecstatic exhilaration. When dance becomes meditation, it flowers into love, and this flowering is a movement toward the divine. By experiencing this

bliss state over and over through music and dance, I gradually became aware of my own divinity, my inner spirit teacher.

I have found that it is very important to learn and preserve traditions but that blindly adhering to rigid patterns prevents the ecstatic experience. It is wiser to find your own creative energy

and let it grow and blossom out of your own substance.

The same concepts apply to the traditional kut ceremony. The kut is a powerful, direct process of purification that cuts through our fear, conflicts, and confusions. Through ecstatic dance, the

shaman helps participants to connect with their own sense of freedom, so they can generate sufficient energy to overcome their obstructions. Fear is transformed into plentiful universal love -

and, suddenly, life is about more than suffering; it is also about experiencing rapture.

What you can learn from the shaman is that it is possible to raise life energy to a level that can open the door to the unknown, after which the endless bliss experience is available. The journey

of ecstasy makes the human mind capable of joyful exploring, discovering, and achieving a higher state of being, and it helps us to understand the art of divine energy'

Mina Otis Haft: Is there anything else you'd like to say about your work and your future plans?

Hiah-Park: My work as a shaman is not bound by any single set of theological, cultural, or historical limits, Since my initiation in 1981, I have achieved a new foundation which is very simple and very profound, and I have been able to communicate it with others. I work at the level of the primordial state, mainly achieved through ecstatic trance. By integrating breath, music, dance, and theater, I set the stage for the transformation of the audience and society.

I've been traveling a great deal since 1988. My future plan is to create a global healing art center, where we can integrate our life resources and bring them into our full awareness, so that

we are able to change. I feel it is most urgent that people realize how much we are separated from our own beings and how far we have gone from our own truth (God).It is necessary to transform

our destructive unconscious behavioral patterns into the simple joy of existence.

My humble aim as a woman and a shaman is to move culture forward by the exercise of spiritual intelligence and the creative process. I believe that art and spiritual endeavors that are founded on

ecstatic experience can contribute to our understanding of life.

SHAMANS DRUM | ©1992 |

Nina Otis Haft is a writer, dancer, and martial artist living in Oakland, California.